The Award

It was sometime during 2015. I was feeling nervous. After promising myself that one day I would make it here, I finally was. I was sitting at the venue where the Lápiz de Acero Design Awards were going to be held that year.

I had followed this publication since my early days studying industrial design. At some point I told myself that one day I would win one of those awards, one day I would prove to myself and others that I belonged there.

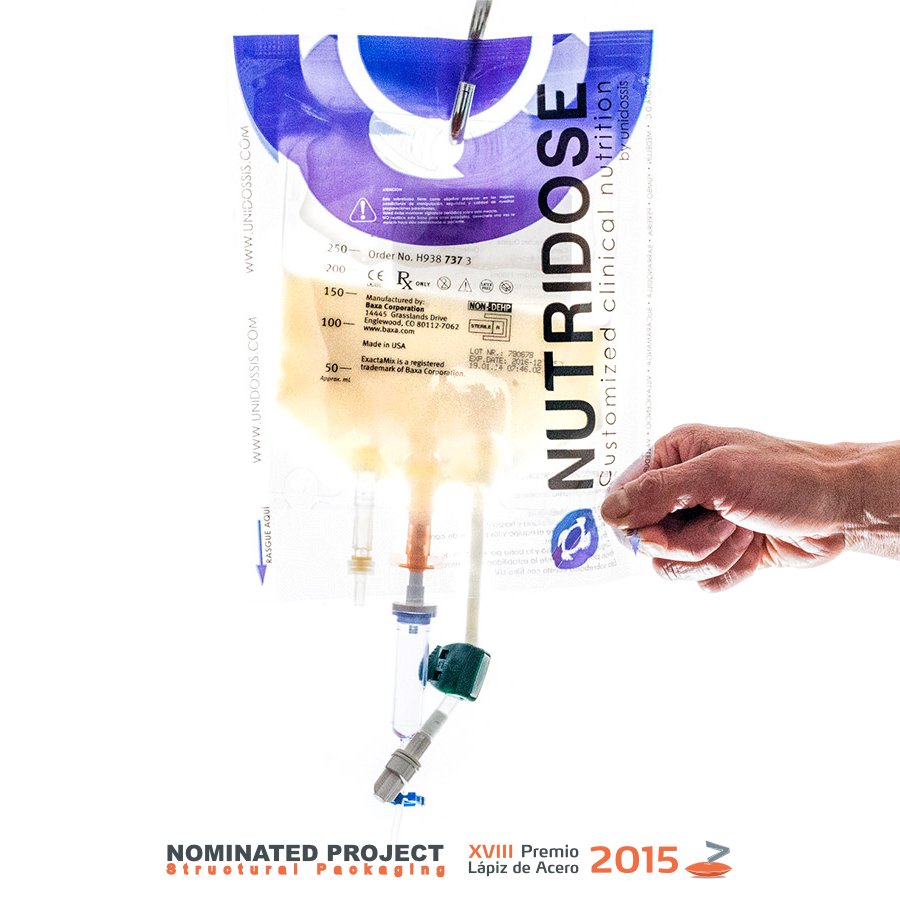

This was my year, and part of the last. I had the chance to focus my work on a product I believed could change people’s lives. Over the past eight months, I worked with a team on providing a solution to avoid vitamin degradation from UV rays in parenteral nutrition.

The initial brief was simple, vague, and interesting. I was asked to find a solution for parenteral nutrition, which is given to patients during long periods. These bags are often covered with black plastic bags or cloth. I was told we needed something better, something cool, a new brand that could stand out the way a Formula 1 car does.

It was a lot to take in. So you want packaging design and branding, that is it right? Yes, was his answer.

Then with the team we started to investigate. Why were they covering them? Was it for aesthetics, or to keep patients from seeing the multicoloured, sometimes bright white liquid inside? What was the real reason?

We found the reason was none of those. The clinical personnel explained that despite the bags where the nutrition was packed already having some UV protection, long exposure to sunlight would still degrade the vitamins inside. This meant the patient would not receive the same quality of nutrients in the morning as in the afternoon.

So we had the reason. This problem was beyond the initial brief. This was not only branding or packaging but helping people’s lives.

We started the project. It took us months of research, brainstorming, prototyping cases, wrapping, and testing to find the simplest way to solve this issue. We needed an extra bag to protect the product. I know it sounds simple, maybe mediocre, but at that stage we had already considered many options like storage cases and cardboard packaging. Each iteration came with a new limitation.

But I felt this time this was my project. I was not going to let any loose end remain unresolved. Over those months, we gathered feedback from clinical staff, experts, and people who worked at the mix compound. Everyone needed something in particular.

It was overwhelming but interesting. This was a real project of design.

Four months into the project, we had arrived at the plastic bag. We had a design we thought would solve most of the issues we had listed during our research, but there was something we could not address yet. The UV protection. We knew the bag could not have any colour. It had to remain clear and without any solid pigment that would interfere with nurses checking the nutrition over time. I felt we had hit a wall. We were running out of ideas, and it seemed we had exhausted every other option.

Until serendipity did its magic.

I do not remember exactly how, but at some point I got the contact of a lamination factory responsible for making potato chip bags. I called them, set an appointment, and started working with them.

I knew chip bags are a lamination of different materials, so I asked if they could do something similar but with one layer providing UV protection. He asked for some weeks to check with his team. Some weeks later, I had in my hands a sample of a very normal looking plastic they made to confirm they could do a four layer lamination, completely transparent and printable.

We had the project. We had a design, materials, and a list of requirements completed. During this time, I also worked in parallel on the brand, the logo, and the colour scheme, and I applied them to the prototypes.

I even turned away a very interesting job offer after showing this project to another designer who would later win this award with the Balígrafo.

We received approval from the company CEO to proceed with implementation and final production. We tested the material in two prestigious universities in Colombia, and both tests were positive. The bag would provide the extra UV protection needed.

We did an industry launch of this product in Cartagena, and it was successfully implemented in Bogotá.

Then I decided to submit this product to the Lápiz de Acero award and see what would happen. Turns out we were nominated. A pharmaceutical mix compound was now among the selected finalists.

It was surprising. A place completely outside the world of creativity, with no big marketing budget and no in house design team, apart from me, was now competing against the biggest brands and studios in Colombia.

Although I let myself dream of a win, I knew it was almost impossible.

I was not wrong. We did not win.

I was upset. I did not want to reach out for feedback. I could not believe a project designed to improve people’s lives had lost to a yoghurt lid, literally a yoghurt lid. I turned my back on design. I lost my faith in the system.

It took me years to understand where the problem was.

It was not our project or product, neither the jury, the award organisation, nor the yoghurt. I was the problem. I had walked ninety nine percent of the way there. My team and I gave everything we could.

But I failed at the end. I could not effectively communicate what this project was about and why I thought it deserved a design award.

When I received the nomination, I was given an extra opportunity to submit more photos of the product along with more information for the jury to understand more. While I did the best I could with the photos to show it in context and in use, I failed to create a compelling document that explained this was more than a transparent plastic bag with a big, really big, logo.

And that was where I failed my team, my friends, my peers, and myself. I could not be bothered to give that one percent extra.

But years later I understood the beauty of this project and the beauty of not winning the award, because from the beginning we had already won. We helped people’s lives improve.

We did not need a trophy to show we excelled at designing something thoughtful. We were already helping people in a critical health state receive better nutrition. Nutridose was about that and was being used in many hospitals.

And that was what mattered. It took me years to see it and understand. I do not need an award to prove to myself that I can create things with substance and meaning. I just need to keep my eyes open, cultivate a creative mindset, and stay curious about the things that happen every day.

And to those who walked with me on this project, Andrea, Christian, Willy, Alberto and Hans, thank you. It was fun, meaningful, and full of learning and experimentation.